The Spiritual Exercises

About the Spiritual Exercises

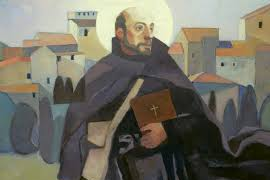

The Spiritual Exercises form the foundation of Ignatian spirituality and the worldwide mission of the Jesuit order of priests. They are rooted in the life experiences of Iñigo Loyola (1491–1556), a bold and ambition-driven Basque nobleman and soldier who underwent a profound conversion to Christian faith while recovering from battle injuries. During his recovery, he read books about the life of Christ and the lives of Christian heroes, leading him to realize that his passionate pursuit of worldly fame would be better directed in service to Christ.

After many years of prayer, self-reflection, discernment, and giving spiritual direction to others—during which he took the name Ignatius and founded the Jesuit Order—he compiled his insights into a spiritual handbook called the Spiritual Exercises. For nearly five hundred years, this handbook has served as a key resource for spiritual directors, guiding those seeking a deeper experience of God’s love.

“Everyone should take the Spiritual Exercises. They arrived at a moment in my life when I was ready to deepen my faith in ways I don’t think I could have done on my own. While I was following the Exercises I felt like I was blessed with a great gift, one that continues to inspire me today. Tom Cashman was the spiritual director and guide I’d been seeking for many years.“

Chuck Appleby – California

Ignatian Spirituality

Ignatian spirituality emphasizes that God is present “in all things” and is actively “laboring on our behalf” to draw us closer to Him. Jesuit educator and author Kevin O’Brien SJ explains that in the Exercises, “Ignatius invites us into an intimate encounter with God revealed in Jesus Christ so that we can think and act more like Christ.”

Increasing Openness to the Movement of the Spirit

In the words of Ignatius, as translated by David Fleming SJ, the Spiritual Exercises “are good for increasing openness to the movement of the Spirit, for helping to bring to light the darkness of sin and sinful tendencies within ourselves, and for strengthening and supporting us in the effort to respond more faithfully to the love of God.” Ignatian spirituality affirms that God is present in all things — in creation, our relationships, our work, our thoughts, and our culture — and in everything we do.

What is the 19th Annotation?

Ignatius developed the Spiritual Exercises to be given by a spiritual director and completed by a retreatant during a thirty-day silent retreat of daily prayer and conferences with the director. The retreatant would leave behind their home and daily responsibilities to retreat at a center or monastery. Today, these Exercises are available at numerous Jesuit retreat centers around the world.

However, Ignatius recognized that many who wished to make the Exercises could not afford to leave their homes and families for an extended period. In response, he developed the 19th Annotation, an adaptation that allows the full Spiritual Exercises to be completed over 32-36 weeks.

The Retreatant and Spiritual Director Working Together

Ignatius requires retreatants to take the Exercises with the guidance of a qualified spiritual director. An Ignatian spiritual director is a faithful Christian called to accompany others on their faith journey. The director has completed formal training in the Spiritual Exercises and has been credentialed to guide others. Additionally, they have engaged in the practice of daily prayer with scripture for at least two to three years, and thereafter.

Ignatian spirituality recognizes that three participants are engaged in the Exercises: God, who initiates and leads the relationship; the retreatant; and the spiritual director. The retreatant and the director meet regularly – usually weekly– in meetings called conferences. During these sessions, the director provides the retreatant with assigned scripture readings, questions, and prayer exercises to complete between conferences. These exercises follow the order prescribed by St. Ignatius and are tailored to the needs and pace of the retreatant’s journey through the retreat.

In each conference, the retreatant shares their experiences of prayer and reflection on the readings. Through careful listening, the director helps the retreatant identify the movements of God that invite them to draw closer to God. The director also assists the retreatant in discerning distractions, temptations, sins, unhealthy attachments, and ego-driven preferences that divert them from drawing closer to God.

At the conclusion of each conference, the director will provide a new set of exercises, along with questions and concrete topics for the retreatant to reflect on and pray about before their next session. Conference sessions at Waypoints Spiritual Direction are conducted online via video conferencing applications. In-person sessions are available if geographically feasible.

The relationship between the retreatant and the director is built on trust and friendship in God. While the director is not the retreatant’s confessor, they help the retreatant respond to God’s invitation to address their sin and may advise the retreatant to go to confession if necessary.

The director does not impose their personal spiritual or religious agenda on the retreatant. Nor does the director provide advice on challenges related to daily life, career, or family matters that are better addressed by a licensed psychologist, mental health professional, or counselor.

The Structure of the Spiritual Exercises

The Spiritual Exercises closely follow the key events in the life and ministry of Jesus, aligning with the liturgical calendar of the Church year. For those beginning the Exercises in September, the Nativity of the Lord is typically contemplated during the Advent and Christmas seasons; the accounts of Jesus’ preaching, teaching, and healing are reflected upon from January to March; and Jesus’ Passion, Resurrection, and Ascension are contemplated from Lent through Pentecost.

By engaging with scripture, prayer, and exercises of the imagination known as meditations and contemplations, the Spiritual Exercises help the retreatant reflect on who they are for God and who God is for them.

The retreatant is not required to begin the Exercises in September. They can be arranged according to convenience and schedule.

The Preparation Days

Three to four weeks before the start of the formal Four Weeks of the Exercises, there are the Preparation Days. During this time, you and your director will get to know one another, and you will establish the spiritual disciplines that will guide you throughout the retreat. You will be introduced to the Principle and Foundation, and the Examination of Conscience (also known as the Examen Prayer), which helps you begin to discern movements in your life. During this time, you will develop the discipline of daily prayer, committing approximately 45 minutes to an hour each day.

The Four Weeks

The Exercises are divided into four sections called “Weeks.” These Weeks do not correspond to a typical seven-day calendar week. Instead, they organize distinct themes of prayer, contemplation, and meditation that help the retreatant experience God’s nearness and grace.

First Week

In the First Week, we reflect on our lives in light of God’s boundless love for us. We focus on who God is and how our response to God’s love may have been delayed or hindered by patterns of sin. We consider our sinfulness knowing that God desires to free us from disordered affections—those attitudes, actions, and possessions that prevent us from fully committing ourselves to God’s service. The First Week ends with a meditation on our commitment to Jesus’ call to follow Him.

Second Week

During the Second Week, through prayers and meditations on scripture—such as Jesus' birth, baptism, the Sermon on the Mount, and his teachings and healings—we learn what it means to follow Jesus as one of his disciples. In our prayers, we ask for an intimate knowledge of Jesus so we can see him more clearly, love him more dearly, and follow him more nearly.

Third Week

The Third Week focuses on meditations on the Last Supper, Christ’s passion and death, and the Eucharist. We see in His suffering the full expression of God’s love for us.

Fourth Week

In the Fourth Week, we meditate on Jesus' resurrection and his appearances to his disciples. We walk with the risen Christ and commit to loving and serving him in concrete ways in our lives and in the world. The Fourth Week concludes with a decision: to change our lives and commit to doing Christ’s work in the world.

Prayer in the Exercises

The Spiritual Exercises teach us how to be in close relationship to God who desires intimacy with us.

We know that for a relationship to be successful, both parties need to know how to listen to one another. Both must give and take; speak and listen. Many of us first learned to pray in one direction only: we may tell God all of our needs (which he knows of already) and then end our prayer likely expecting God to respond in full and form to our request. For us to understand more of what God wants for us, we must learn to wait upon God by listening and watching for God’s initiative and response to our prayer.

The Spiritual Exercises present three methods of prayer that may be new to retreatants — meditation and contemplation. Kevin O’Brien SJ succinctly defines meditation and contemplation in his book, The Ignatian Adventure:

In meditation we use our intellect to wrestle with basic principles that guide our life. Reading scripture, we pray over words, images, and ideas. We engage our memory to appreciate the activity of God in our life. Such insights into who God is and who we are before God allow our hearts to be moved.

Contemplation is more about feeling than thinking. Contemplation often stirs the emotions and enkindles deep desires. In contemplation, we rely on our imagination to place ourselves in a setting from the Gospel readings or in a scene proposed by Ignatius. . . In the Exercises, we pray with Scripture; we do not study it.

Application of the Senses is a third type of prayer used throughout the Exercises, which John J. English SJ, describes as “a method of contemplating with our whole being.” Where, with contemplation we use our intellect to deeply consider the scriptural truths, and with meditation we engage our hearts and emotions, with application of the senses “the totality of our being becomes involved.” We use our imaginations to see, hear, smell, touch and sense the presence of the scripture scene we are praying.

Discernment of Spirits

As our intimacy with God grows, we become more aware of interior movements that influence our lives. Ignatius called these movements “motions of the soul.” They include emotions, feelings, desires and inclinations, attitudes and actions, attractions, and revulsions. Sometimes we sense them coming from within us. At other times they seem to arrive from outside us. Discernment of spirits involves becoming sensitive to these movements, recognizing them and understanding their source, and where they lead us.

The website ignatianspirituality.com explains these well:

Ignatius believed that these interior movements were caused by “good spirits” and “evil spirits.” We want to follow the action of a good spirit and reject the action of an evil spirit. Discernment of spirits is a way to understand God’s will or desire for us in our life.

Talk of good and evil spirits may seem foreign to us. Psychology gives us other names for what Ignatius called good and evil spirits. Yet Ignatius’s language is useful because it recognizes the reality of evil. Evil is both greater than we are and part of who we are. Our hearts are divided between good and evil impulses. To call these “spirits” simply recognizes the spiritual dimension of this inner struggle.

Consolation and Desolation

In Ignatian Spirituality, feelings stirred up by good and evil spirits are described as consolation and desolation.

Spiritual consolation is an experience of being so deeply touched by God’s love that we feel compelled to praise, love, and serve God, and to help others as best as we can. Spiritual consolation fosters a deep sense of gratitude for God’s faithfulness, mercy, and companionship in our lives. In times of consolation, we feel more alive, more connected to God, and more at peace with others.

Spiritual desolation, by contrast, is an experience of the soul in turmoil or darkness. We may feel assaulted by doubts, bombarded by temptations, and mired in self-preoccupation. These feelings are often accompanied by restlessness, anxiety, and a sense of disconnection from others. In Ignatius’s words, desolation “moves one toward lack of faith and leaves one without hope and without love.”

The key question in interpreting consolation and desolation is: Where is the movement coming from, and where is it leading me? Spiritual consolation does not always equate to happiness, and spiritual desolation does not always mean sadness. Sometimes, an experience of sadness can lead to a moment of conversion or a deeper intimacy with God. Times of human suffering can also be moments of great grace. Similarly, feelings of peace or happiness can be illusory if they pressure us to avoid necessary changes in our lives.